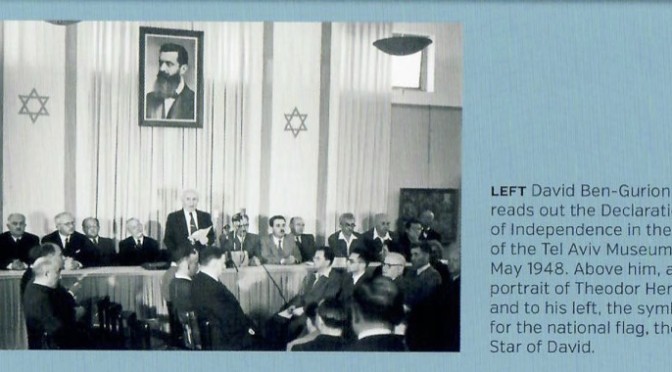

At five o’clock on the afternoon of 14 May 1948, in the main hall of the Tel Aviv Museum, a ceremony took place that inaugurated the State of Israel. The ceremony began with the singing of the Jewish anthem “Hatikvah”. A few moments later David Ben-Gurion, as Prime Minister and Minister of Defence of the newly created provisional government, put his signature to Israel’s Declaration of Independence. As the other signatories completed their work, “Hatikvah” was played again, by the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. Palestine was no more. Although the last of the British troops and administrators were not to leave the country until the following day, May 15, the day of their departure was a Saturday – the Jewish Sabbath – a day on which those religious Jews who would have to sign the Declaration could not wield a pen. Indeed, according to Jewish tradition, the Sabbath began the previous evening – that is, at sunset on May 14. Hence the Friday afternoon declaration.

“For two thousand years the revival of the Jewish State in Palestine had been the passion and dream of a scattered people,” Walter Eytan wrote ten years later. The decision to declare independence, he commented, “was Israel’s alone. The courage to take it grew from the stored-up anguish of those two thousand years. The debate which was still going on in the United Nations might have been a metaphysical disputation for all the effect it had on the events in Tel Aviv.”

The declaration opened by describing the Land of Israel as the birthplace of the Jewish people, and looking back at the land’s distant past. “Here their spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped. Here they first attained to statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance, and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.” They had “kept the faith” with the land during all the years of dispersal, “and never ceased to pray and hope for their return to it, for the restoration in it of their political freedom.” The declaration continued:

“Impelled by this historic and traditional attachment, Jews strove in every successive generation to re-establish themselves in their ancient homeland. In recent decades they returned in their masses. Pioneers, ma’pilim – immigrants coming in defiance of restrictive legislation – and defenders, they made deserts bloom, revived the Hebrew language, built villages and towns, and created a thriving community, controlling its own economy and culture, loving peace but knowing how to defend itself, bringing the blessings of progress to all the country’s inhabitants, and aspiring towards independent nationhood.”

The declaration went on to recount the historic stages, starting with the First Zionist Congress in 1897, the Balfour Declaration of 1917, and the League of Nations Mandate, which gave “international recognition to the historic connection between the Jewish people and Eretz Yisrael, and to the right of the Jewish people to rebuild its National Home.” The “catastrophe which recently befell the Jewish people – the massacre of millions of Jews in Europe” was, the declaration stated, “another clear demonstration of the urgency of solving its homelessness by re-establishing in the Land of Israel the Jewish State, which would open the gates of the homeland wide to every Jew, and confer upon the Jewish people the status of a fully privileged member of the comity of nations.” Through the partition resolution of November 1947, the recognition by the United Nations “of the right of the Jewish people to establish their own State is irrevocable.”

Such was the preamble. The document then went on to “declare the establishment of a Jewish State in the Land of Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.” Until that moment, very few indeed of those listening to the broadcasting of the declaration knew what the name of the State was going to be. Since the partition resolution half a year earlier, many different names had been proposed, among them Zion, Ziona, Judea, Ivriya and Herzliya. Postage stamps printed in advance in anticipation of the declaration of statehood were marked “Doar Ivri” (Hebrew mail) since no one know what the name would be.

The new State had its name. Of of its earliest civil servants, Walter Eytan, has commented:

“The moment the name was proclaimed, everyone realized instinctively that it could in fact have no other.

“The children of Israel, the people of Israel, the land of Israel, the heritage of Israel, all these had existed, in reality and metaphysically, for so many thousands of years, they had exercised such influence on the evolution of mankind that the State of Israel was their logical consequence and culmination.

“Ben-Gurion’s choice of name was hailed as a stroke of genius; in fact it arose out of the innermost historic or tribal consciousness of us all.

“There could have been no more effective introduction of the new State to the world. ‘Israel’ on its visiting-card was as eloquent as could be: it was so evocative and so immanently true that nothing more needed to be said. It made obvious to the world not only who we were but that we were what we had always been, and that if the State of Israel as such was a newcomer on the international scene, it was in fact but the natural outward form, in modern terms, of a mystery and a people whose roots went back to the earliest ages of man.”

The Declaration of Independence continued with an assurance that Israel would be open for Jewish immigration, and for “the ingathering of the exiles”. It would be based on “freedom, justice and peace, as envisaged by the prophets of Israel.” It would ensure “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants, irrespective of religion, race or sex,” and would guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture. It would be faithful to the Charter of the United Nations (of which it was not yet, of course, a member).

The declaration went on to appeal to the Arabs of Israel (the borders of which were nowhere defined) to “preserve peace and participate in the upbuilding of the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship” and “due representation in all its provisional and permanent institutions.” As to Israel’s Arab neighbours, the new State extended to them and their peoples “an offer of peace and good neighbourliness.” The State of Israel was “prepared to do its share in common effort for the advancement of the entire Middle East.”

The declaration ended with an appeal to the Jewish people “throughout the Diaspora to rally round the Jews of the Land of Israel in the task of immigration and upbuilding, and to stand by them in the great struggle for the realization of the age-old dream – the redemption of Israel.”

An excerpt: Israel, A History ©Martin Gilbert

Subscribe to Sir Martin’s Newsletter & Book Club

Follow and share Sir Martin with your friends

Twitter @ SirMartin36 and Facebook Sir Martin Gilbert