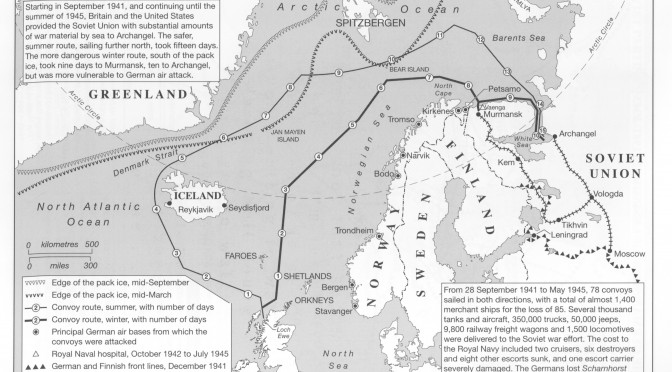

Photo: Route of Anglo-American aid to the Soviet Union to keep them in the Second World War, from Sir Martin’s Routledge Atlas of the Second World War

700 words / 3 ½ minute read

The war was about to take a dramatic turn. On 22 June 1941 Hitler ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union, his ally for almost two years. Churchill feared that a German victory would leave Hitler free to attack Britain, making use of the raw materials and oil reserves of Russia. Desperate to avert a German victory in Russia, he not only gave the Soviet Union large quantities of military equipment but also persuaded Roosevelt to do likewise.

…

Formal talks between Churchill and Roosevelt began on August 11. After Hopkins told them of his recent meetings with the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, Roosevelt agreed to give immediate aid to the Soviet Union “on a gigantic scale”. He also agreed to Churchill’s suggestion to send an Anglo-American mission to Moscow to settle the nature and scale of munitions and other supplies to the Soviet Union by Britain and the United States “conjointly”.

…

One burden for Churchill throughout the autumn of 1941 was that British and American aid to the Soviet Union, judged essential by both Churchill and Roosevelt to prevent a German victory in the East, ate into the whole range of British supplies from America for which Churchill had fought so hard. “The offers which we are both making to Russia,” Churchill telegraphed to Hopkins on October 2, “are necessary and worthwhile,” but there was “no disguising the fact” that these offers made “grievous inroads into what is required by you for expanding your forces and by us for intensifying our war effort.”

Among the commitments to the Soviet Union was one that intensified the dire shortage of Anglo-American merchant shipping. Because the Soviet Union had almost no merchant shipping capability, Churchill and Roosevelt were providing shipping from their respective merchant navies on a substantial scale. This enabled the transport to the Soviet Union of half a million tons a month of cargo: food, oil and war material imports, medical supplies on a vast scale, including more than ten million surgical needles, half a million pairs of surgical gloves, four thousand kilograms of local anaesthetics, and more than a million doses of antibiotics. These had only just become available in clinical form. Soviet troops were to be their first beneficiaries.

…

1942: As a result of his two visits to Washington, Churchill had secured a series of Anglo-American joint ventures. On June 27 the first Russia-bound convoy with a joint Anglo-American escort – two British and two American cruisers – sailed from Iceland. Three weeks later, Hopkins, Marshall and Admiral Ernest J. King – Chief of Naval Operations – reached London to determine Anglo-American strategy for the end of 1942. Churchill, his War Cabinet and military advisers opposed the American preference – a landing at Cherbourg – as it lay at the limit of fighter cover from air bases in Britain. The Americans deferred to this, agreeing that an attack on French North Africa would be that year’s joint Anglo-American effort to help the Soviet Union, then facing a renewed German offensive in the direction of Stalingrad and the Caucasus. …

Stalin was angered by the abandonment of the Cherbourg plan. Churchill decided to fly to Moscow and explain the new strategy to him, and asked Roosevelt if Averell Harriman could travel with him. Churchill explained: “I feel it would be easier if we all seemed to be together. I have a somewhat raw job.”

….

The Moscow visit lasted five days. After Churchill had explained the North African landing to Stalin in detail, Stalin understood their potential, telling Churchill: “May God help this enterprise to succeed.”

And a word of warning, from 1956:

In his letter for Eisenhower, Churchill suggested that the horror of nuclear war meant that the Soviet Union would not make war, knowing it would suffer missions of deaths among its own people. Eisenhower disagreed. “You will remember,” he wrote, “that in 1945 there was no possible excuse, once we had reached the Rhine in late ’44, for Hitler to continue the war, yet his insane determination to rule or ruin brought additional and completely unnecessary destruction to his own country; brought about its division between East and West and his own ignominious death.”

Excerpts from Churchill and America

Join Allen Packwood, director of the Churchill Archives at the Sir Martin Gilbert Learning Centre on December 2nd for a lively and learned discussion of this book, Churchill And America:

Read: Churchill and America