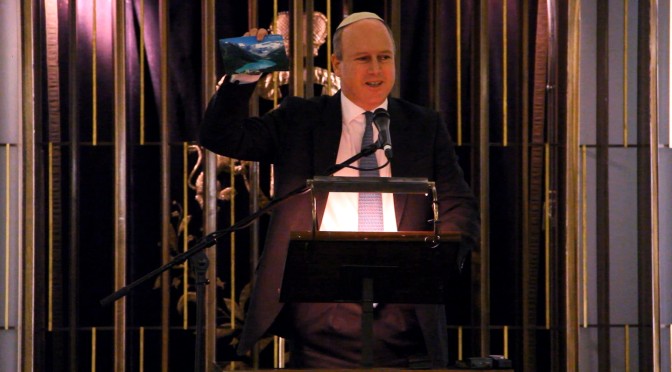

Sir Martin Gilbert Memorial, 24 November 2015

I stand humbly before you all today, as does the Churchill family. After all, more than anyone else, we owe Martin and all his family the most unimaginable, incalculable gratitude for his outstanding biography of my great-grandfather, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, and for his many other works on other aspects of Churchill’s life.

Over the years I have had the privilege of getting to know Martin well, enjoying a friendship punctuated with laughter and, of course, engaging in historical debate with each other. Indeed I have something with me today which many of you I am certain also treasure, namely one of the many postcards Martin sent me over the years. Even while he was travelling, he never forgot his friends.

It was Lady Diana Cooper who introduced Martin Gilbert to my grandfather and namesake, Randolph Churchill. Randolph had been given the task of writing the official biography of his father at the end of the 1950s.

The ‘Great Biography’ has always been part of my life. As a child, one of the highlights each year was our family Christmas, which we spent at my parents’ farmhouse in Sussex. We were often joined by my great-grandmother, Clementine, and also by Peregrine Churchill, the younger son of Churchill’s brother, Jack.

During mealtimes the discussion would inevitably turn to the biography and the pace of its progress! My father, Winston, regaled us with stories of how the biography began and of his own father, Randolph, gathering together the resources at his beautiful but chaotic Georgian house, Stour, in East Bergholt where the top floor was turned into a literary factory.

There were many house parties at Stour, where more often than not the house guests were provoked by my grandfather who, fortified by scotch and claret, relished debate and argument. He often found that, by the time he had awakened in the morning, his guests had already left! That option was not available to his team of young researchers which included Andrew Kerr, Michael Wolff, Tom Hartman and, of course, Martin Gilbert, all of whom grew up on a diet of Churchill excitement, debate and endless energy.

Stour became the nerve centre of the biographical operation and Randolph’s team of researchers. Michael, formerly a journalist in the Beaverbrook Empire, was appointed Director of Research and was consequently Randolph’s right-hand man, spending much of his time at Stour. Martin soon joined the team of “young gentlemen”, as they were known. Although Martin was based at Merton College, Oxford, where he was a Fellow, he was always eager to help and fitted this obligation in amongst his many other projects.

Martin was interested in illustrating his works with maps and even published fifteen atlases, all with such success that he was able to build a house at North Hinksey, which he called The Map House. That house was designed around one large room, the center piece of which was a desk which extended from one wall to the other, on which Martin laid out the Churchill documents.

Randolph used to say that Martin worked “like a tiger for research”. He had an enormous capacity for absorbing the essence which ‘The Boss’, as Martin called Randolph, needed. His researches went far beyond the Muniment Room. It was a hallmark of Martin’s life that he was thorough, relentless, and unwilling to be satisfied with anything less than everything. What he couldn’t find, either at Stour or at Oxford, he would go and obtain by interrogating aging, even aged politicians who had worked with my great-grandfather, journalists, military men or others who he believed would be able to add to the Churchillian story.

As time went by, Randolph’s health deteriorated, his temper became more fragile, and progress on the great work slowed down. Randolph died a scant three years after the death of his father. He had seen the publication of two volumes of the main work with three companion volumes containing original documents, and was working on volume three when he died.

Randolph had been extremely fortunate to enjoy the respect of his supporting team, which had enabled him to get this far and set the production of the Great Biography in motion. Eventually Martin took over the reins and completed the colossal work, bringing the total to eight main volumes – three more than originally planned. His support, respect and admiration for my grandfather are evident in a letter Esther sent to me a few months back:

‘Randolph, while looking for something else, I found this that Martin had written in a letter to Sir Isaiah Berlin about your grandfather. The letter is dated 6 June 1969. I read it and thought of you and thought you might like to know what Martin had written’:

Today is also the first anniversary of Randolph’s death; and I am on my way this morning to his grave. It has not been easy taking up his work. But now that I have begun the actual writing of volume three, which covers the First World War, I feel a new upsurge of energy and inspiration.

When I began to work for him I felt a great deal of fear mingled with a certain amount of awe; after six years the fear had been replaced by admiration and the awe by affection. And then he was gone: and neither the honour of having been chosen to carry on his work nor the excitement, variety and interest of the work itself can ever obliterate the pain of his departure.

I have a number of very happy memories of the joy, humour and fun that Martin relished. He held his 70th birthday at the English-Speaking Union and he entertained us with many of his reminiscences. After all, Martin’s mind was like a steel trap, capturing and never forgetting the rich and fascinating experiences he had lived, many of which he recounted in his most personal of Churchill-related volumes, namely, In Search of Churchill. But on the occasion of his 70th birthday, he had also picked out – and we sang together – the soldiers’ songs as they headed to the Great War.

Martin’s interest in life was boundless. In addition to his dedication to Churchill, he was committed to the history and stories of the Jews, Israel and the Holocaust. In the broadest sense Martin was the ‘chronicler of the twentieth century’.

I was entranced with his account of how he was evacuated from Liverpool to Toronto, Canada when he was not yet four years old. Then, when he was seven and a half years old, he returned on board the Mauretania to the Liverpool docks, having not seen his parents once in the intervening wartime period.

The Churchill family owes Martin the greatest debt of gratitude for recording and preserving the record of Churchill and all those around him so faithfully that we can better understand his life and times and reach our own conclusions.

Martin understood completely the context and the pressures of the time – he certainly mapped that history most clearly so that all of us can see it.

I would also add that with the loss of my own father a few years ago, the challenge of upholding my great-grandfather’s legacy has been so much less of a challenge and more of a joy as I constantly delve into the biography and other accounts, including Martin’s remarkable account of Churchill and the Jews, which sets the record straight and allows me with confidence to ensure that the historical record is preserved rather than being manipulated by others for their own agenda.

In an important respect, Martin is and always will be with me, and I feel his influence every day.

As the years go by, the Great Biography of Churchill, started by Randolph and completed by Martin, will go down as one of the greatest biographical accounts ever written. It is certainly one of the longest, but that reflects the fact that Martin loved accuracy and detail, and always sought the truth of the matter. He has enabled history to judge Churchill fairly because he has placed the story fully and precisely in our hands. Gilbert’s biography of Churchill is peerless and our family will never forget the debt we owe him and all his family.

Churchill said: ‘History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it‘. We are so lucky that Martin has done the equivalent for Churchill, of whom he has bequeathed to us and future generations the fullest account. And today the Churchill family and, I am sure, all of you collectively salute Martin’s great literary and historical achievement.

Thank you.